Let’s get something straight,” the politician told me, “we are now owning you.” Though this was meant as a warm welcome, hearing it from an eminent state official made me wonder what I had got myself into. Olivia Grange, Jamaica’s influential minister of culture, gender, entertainment and sport, looked me in the eyes: “You are Jamaican now, you are part of us.”

I met Grange last April, on a hot day in Port Maria in St Mary parish on the northern coast of Jamaica. Both of us had come to the town to commemorate the second annual Chief Takyi Day. Grange had established the holiday in 2022, instigating the government’s proclamation that henceforth 8 April would honour Takyi, or Tacky, as he was generally called in English, the best-known leader of the largest uprising of enslaved Africans in the 18th-century British empire. I was invited to the event because I had written the first book about Tacky’s revolt.

I was honoured, but I can’t say that I was comfortable. It was a sweltering day at the start of mango season, and I was sweating in my suit and tie. A crowd of about 80 people sat on folding plastic chairs under a canopy that kept us shaded but also blocked any breezes that might have brought relief.

The heat did not stifle the festive mood. Roots reggae music vibrated from the sound system. Two troupes of dancers performed traditional choreography between speeches by politicians and activists. Locals from the area were dressed up for the celebration, many of them in the green, gold and black of the Jamaican flag, and the crowd seemed excited. St Mary is a 90-minute drive over the Blue Mountains from Kingston, Jamaica’s bustling capital, and while tourists sometimes come to visit the parish’s beautiful coves and beaches, the region is lightly developed and materially impoverished. An appearance by a cabinet member such as Grange was a big deal, as was the event itself: it signalled official recognition of local history, which many people hoped would gain national attention.

My presence, as a Harvard professor and the author of the most extensive scholarly treatment of the slave uprising, was supposed to add the authority of a global institution to the occasion. But the event was also a big deal for me. Grange and others involved in the commemoration of Tacky’s rebellion had cited my book as an inspiration for the holiday, and I’d been flattered when the organisers asked me to give remarks from the perspective of an American historian.

Academics don’t often get to see the impact of their books in the world, and initially I was just as eager as the locals to see Tacky celebrated with a national holiday. A historian’s job is to help us remember the past, and for someone in my line of work there are few greater satisfactions than knowing that you helped bring some previously obscure slice of history into common awareness.

During my time in Jamaica, however, I came to realise that the situation was not as simple as I’d imagined, and that my own feelings were far from settled. This was a national effort, and I was not a Jamaican national. I was grateful to hear the minister’s welcoming words, but they weren’t quite true. I was a part of something, though maybe not something I fully understood or agreed with. Along with Black people throughout the Americas, Jamaicans and I together belonged to the African diaspora. But as with scattered people everywhere – Jews, Armenians, Chinese, south Asians – there was no guarantee of mutual understanding or accord. There was nothing predetermined about how we would commemorate our common history, and the history of Tacky’s revolt was no exception.

In the mid-18th century, Jamaica was Great Britain’s most profitable colony in the Americas. Not coincidentally, it was also the colony that exploited enslaved labour most aggressively. About 90% of the population, around 150,000 people, lived in bondage, and their work made their enslavers stupendously rich. The island society was tumultuous, with frequent uprisings of varying scale and intensity, some of which threatened the very foundations of imperial power.

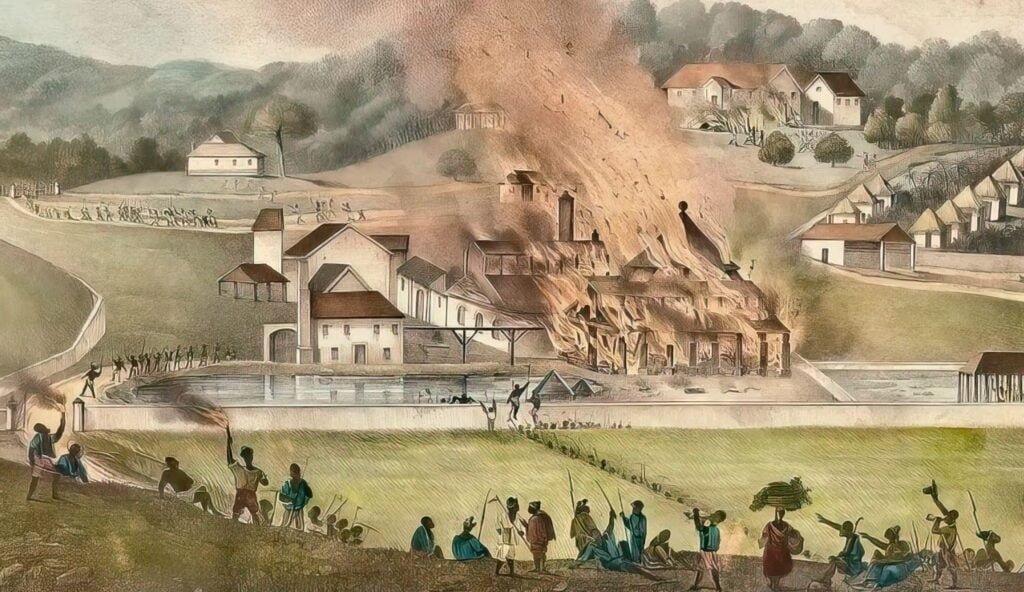

Tacky’s revolt, as it has come to be known, began in the parish of St Mary in early April 1760, when enslaved Africans hailing from the region that is now Ghana attacked and overwhelmed Fort Haldane, the British garrison overlooking Port Maria harbour. From there the rebels made their way through the agricultural heart of the 235 sq mile (600 sq km) district, liberating people and setting sugar plantations on fire as they went. Their numbers swelled into the hundreds as they fought off planter militias and British army regulars.

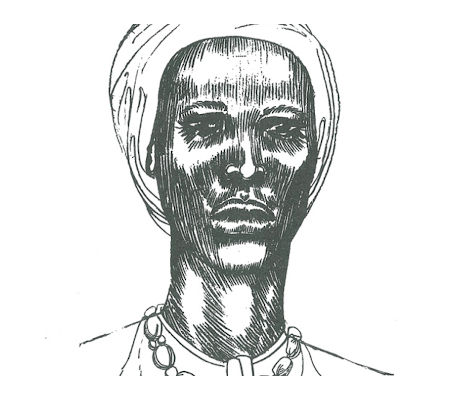

Not much is known about Tacky himself. Judging from his name, which can mean “chief” in the Akan and Ga languages, he appears to have had some significant political or military standing before he was taken from the Gold Coast of Africa by force and put to work on a plantation in St Mary. His role as a principal leader of the uprising that would bear his name was recorded by Edward Long, the English enslaver historian who, in 1774, published an account of the rebellion in his three-volume History of Jamaica.

In my own account, however, which drew on records from archives in several countries, Tacky was just one of many leaders of the rebellion, and perhaps not the most important one. Though he led the early attacks from Fort Haldane to Downes’ Cove, about 20 miles from Port Maria, he was killed soon thereafter, and his decapitated head was put on public display in Spanish Town, then the colony’s capital.

The British largely quelled the uprising in St Mary within two weeks, but the fight for freedom spread throughout Jamaica, ultimately engulfing the entire island. Some of the fiercest clashes took place in the parish of Westmoreland, on the south-western end of the island. Combatants on each side gave no quarter, slaying each other with muskets, cutlasses, knives, blunt objects and bare hands. Over the course of 18 months, the rebels killed 60 white people and destroyed an enormous amount of property. During the suppression of the revolt and the repression that followed, more than 500 Black men and women were killed in battle, executed or driven to suicide. The colonial government banished another 500 from the island for life.

The slave rebellion took place in the midst of Britain’s seven years’ war with France and other European rivals. While the British emerged from the war victorious, with vast new territories and resources, the disruption inspired a series of British imperial reforms that were meant to tighten the administrative control of the empire. These reforms, in the shape of new taxes, regulations and military deployments, indirectly provoked the North American rebellion of 1776. But the slave revolt also led to a burst of colonial legislation to curtail the trade in potentially dangerous African captives, and the brutal crackdown generated a wave of sympathy in some sectors, ultimately helping to turn the British public against the Atlantic slave trade, which Britain outlawed in 1807.

Source: Guardian News & Media